CURRENTLY WIP

The goal through optimal taxation is to minimise distortions and maximise a social welfare function subject to economic constraints. We will assume the social welfare function is of the linear utilitarian kind to maximise average utility amongst individuals, although other options are possible.

Introduction

Regardless of your personal views regarding the amount of taxation you want in society, optimal tax theory matters to everyone - and it’s important to understand it. It doesn’t matter if you’re a ‘tax is theft’ libertarian or a tax fetishising social democrat - some amount of tax is necessary in society. Therefore, I think it’s pretty important that our tax system should be efficient as possible.

Assumptions

It wouldn’t be economics without assuming away every aspect of realism.

-

Everyone in society has the same preferences over consumption and leisure - homogenous preferences

-

A society’s tax system should be chosen so that it maximises a utilitarian social welfare function subject to a set of constraints

- The social welfare function cares only about average utility - it takes the linear form

- I may write an entirely seperate post about social welfare functions, it’s the one of the few areas in mainstream economics that actually involves ethics and normative value judgements. While economists tend to use the utilitarian form by default, there are viable alternatives - covered by welfare economics and economists such as Amartya Sen - for the curious.

-

The set of constraints that the tax system is subject to is an extremely important decision to make, with differing constraints having many different tax implications. Differences in income is an obvious constraint, we simulatenously want people to both pay more in tax the more income they make AND don’t want the tax to alter behaviour by making people work less. This trade-off is a huge component to optimal tax theory.

-

Let’s assume a starting position with no constraints as an example, here the optimal tax is simply a lump sum tax. Everyone is taxed based on a fixed amount, no one can do anything to change their liability and therefore the tax does not distort behaviour. This example is perfect to analyse another fundamental aspect of tax theory: the equity-efficiency trade-off. It is completely prioritising economic efficiency (no distortion of behaviour) and disregarding equity (everyone pays the same tax, regardless of characteristics such as income). I will now cover these both in more detail.

Efficiency

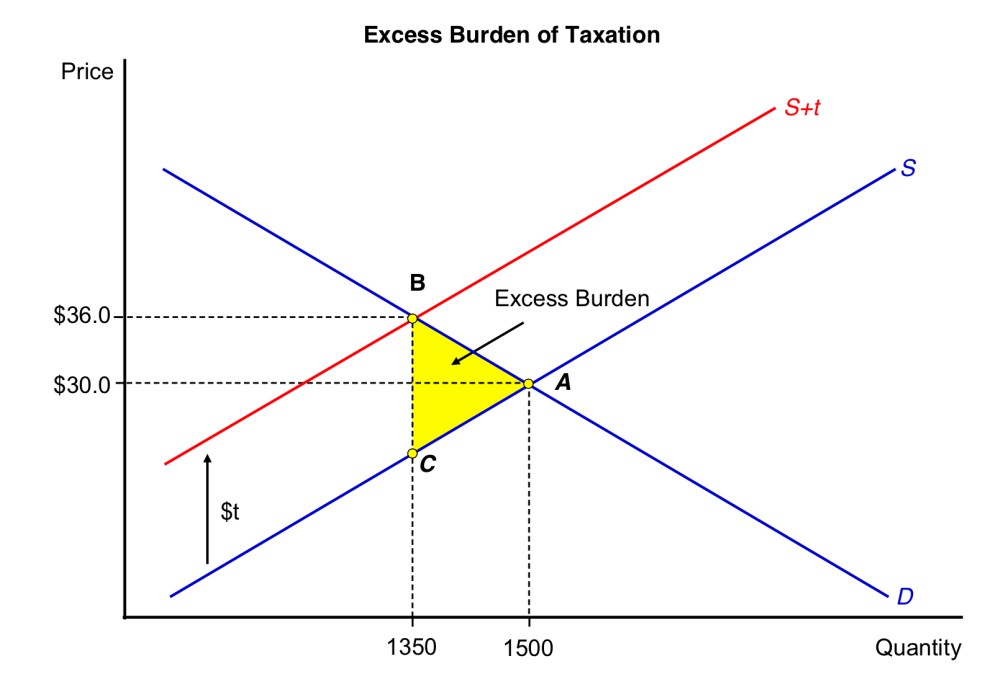

When I make mentions of how taxes can alter behaviour and change incentives, this is all related to the economic efficiency of the tax. It’s pretty intuitive to understand how in general, applying a tax to a good or service will distort behaviour, resulting in an inefficient outcome where economic value is lost. The loss of economic value is called the deadweight loss (or excess burden) from applying the tax.

- In the below econ 101 style figure, you can see that when a tax is imposed, the supply curve shifts upward, the new equilibrium price is at B

- The change to a higher price and lower quantity at point B is the deadweight loss, representated by a yellow triangle

- The change to a higher price and lower quantity at point B is the deadweight loss, representated by a yellow triangle

Equity

Equity matters. A lot of people think economics is only about considering efficiency and chasing it at all costs, but we have lots of tools to consider equity. Many having been a core part of the microeconomics curriculum for decades.

The two fundamental theorems of welfare economics are key here. The first theorem states that in economic equilibrium (with some strict market assumptions), the markets will be Pareto optimal (a market outcome where no further exchange would make one person better off without making another person worse off).

The second theorem states that any Pareto optimal outcome can be supported in economic equilibrium - resources can be reallocated to improve equity while retaining efficiency. Maximising the social welfare function is how we go about getting equity to the (subjective) optimum level.

Equity within optimal tax theory has additional considerations, both horizontal and vertical equity. Horizontal equity aims to impose the same tax burdens across two people with equal abilities to pay. Vertical equity aims to distribute tax burdens fairly across people with different abilities to pay. This follows from the principle that as a person consumes more, the additional pleasure they get from each additional unit of consumption decreases - diminishing marginal utility of consumption. The heterogeneity in taxpayers’ abilities to pay poses a significant challenge for designing optimal taxes.

The equity problem of lump sum taxes could be solved if the tax was contigent on ability to pay. Governments in real life can’t directly observe ability, so this is useless for us.

Preface to the Lessons

Soon I will be covering and summarising all of the 8 lessons from the Mankiw et al., 2009 paper that covers significant conclusions gathered from the advances in optimal taxation theory and empirical evidence. Before that, I want to tie a bow by introducing a model that incorporates multiple fundamental tax policy design concepts that I mentioned earlier. The Mirrlees framework (1971). This framework is a model that provides a theoretical basis for optimal tax design that incorporates unobserved heterogeneity among taxpayers, incentive effects (taxing income discourages working), and diminishing marginal utility of consumption (maximise utility by taxing those of high ability and giving transfers to those of low ability).

As we cannot target ability (income is a very imperfect proxy for ability), imperfect information necessarily impedes maximising utility by taxing and redistributing. The solution to this relies on the revelation principle, a fundamental result in game theory. Put simply, the tax system has to provide sufficient incentive for taxpayers with high ability to keep producing at levels that correspond to their ability - which clashes with the goal to target this group with higher taxes.

The Mirrlees framework is a classic model in public finance that helps tremendously with optimal tax design, it allows us to consider many different types of tax systems that can be realistically implemented. However, the amount of complexity in the model trying to balance incentives so people produce in accordance with their level of ability makes the optimal tax problem significantly more difficult.

The good news is that it has been over 50 years since the original paper was written! There have been lots of progress made using the Mirrlees framework and on optimal tax theory as a whole.